Moving is always a nightmare, but I thought I was handling it pretty well — until the leg of my bedside table snapped off, and I absolutely lost my mind. Not in a normal, “Ugh, what a hassle” way. No, I stood in the middle of my new Virginia bedroom, cradling the broken leg like a wounded limb, sobbing as if my life had just been upended. Which, I guess, in a way, it had.

My parents, who had spent the entire day hauling boxes and assembling furniture, stared at me in exhausted confusion. “We can fix it,” my dad offered in response to my total emotional collapse. But I wasn’t crying about the leg. I was crying because my grandfather had built that table for me, and somehow, I hadn’t realized how much I needed it to stay whole.

Material culture sneaks up on you. It’s easy to think of history as something grand, held in museums or passed down with deeds of gifts or wills. But history lives in the common objects that tether us to where we’ve been and who we come from. The things we touch, use, and repair become extensions of ourselves — our dedication, our love, our need to create permanence in an impermanent world.

My bedside table is not just a table. It is my grandfather; his presence in something solid and familiar.

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s The Age of Homespun argues that objects — especially domestic, handmade ones — carry memory and identity. But Ulrich doesn’t just examine these items as static historical artifacts; she reveals them as dynamic narratives, each piece telling a complex story of human experience. A simple linen tablecloth becomes more than a decoration — it’s a testament to the work of women, a record of economic survival, and a chronicle of domestic creativity.

For women in early American households, these objects were survival mechanisms disguised as everyday items. A carefully woven textile wasn’t just cloth but a financial strategy that interlaced the space between domestic spheres and the broader economic systems they were shut out from. Each stitch, each carefully turned piece of wood represented the tactical work and skills of unheralded artisans.

And there’s history in it all.

History carved into wood and woven into fabric, crafted not just for utility but as a kind of storytelling — one that you can see and feel. And just like the items Ulrich describes, the table my grandfather built was more than mere functionality. It’s a testament to his labor, a piece of family history, a bridge between the past and the present. My grandfather, like the women Ulrich writes about, didn’t see his work as an heirloom in the making. He built because his hands knew how. Because this was his language, his way of providing. He wasn’t overly sentimental about the things he made. But that’s the thing about material culture: we assign meaning later.

As decades pass, objects take on importance beyond their function. What was once practical — a loom, a handwoven cloth, a sturdy table — becomes something else entirely: a link, a testament to care and continuity, a marker of survival. Ulrich describes how an old spinning wheel, once an ordinary tool of daily life, became a relic of a lost way of being, infused with significance only in hindsight.

My table began as something useful — built simply because I needed it — but over the years, it transformed. No longer just furniture, it became a symbol of family, love, and the quiet ways people shape us long after they’re gone. A man builds a table for his granddaughter, never imagining that one day, she will carry it across state lines and only understand its true worth when she’s forced to mend it.

In that moment, when the leg broke, I saw all the years of connection that had accumulated in the grains of the wood like dust. And I felt heavy. Not just a physical weight but the weight of memory and attachment. And I now know that it would be a damn shame to hide the imperfections of this piece — this seemingly living organism. The flaws are a map of our unexpected journey. So, I don’t care if it’s a little worse for wear. That it wobbles. That one drawer sticks. The wood and paint are scuffed, bearing the marks of years, of hands that have opened and closed it a thousand times, of all the moments it’s witnessed and absorbed.

It’s not perfect. Neither was Pop, though he was pretty close. And I think I’d like to spend the rest of my life slamming the drawers shut and watching it disintegrate little by little as I age. Because it’s an honor to lay my head alongside this tangible connection to him, to his craft, to the proof that something built with care, even when it breaks, can still stand.

And if it stands, so do I.

If you made it this far, click that itty-bitty digital organ! ❤️

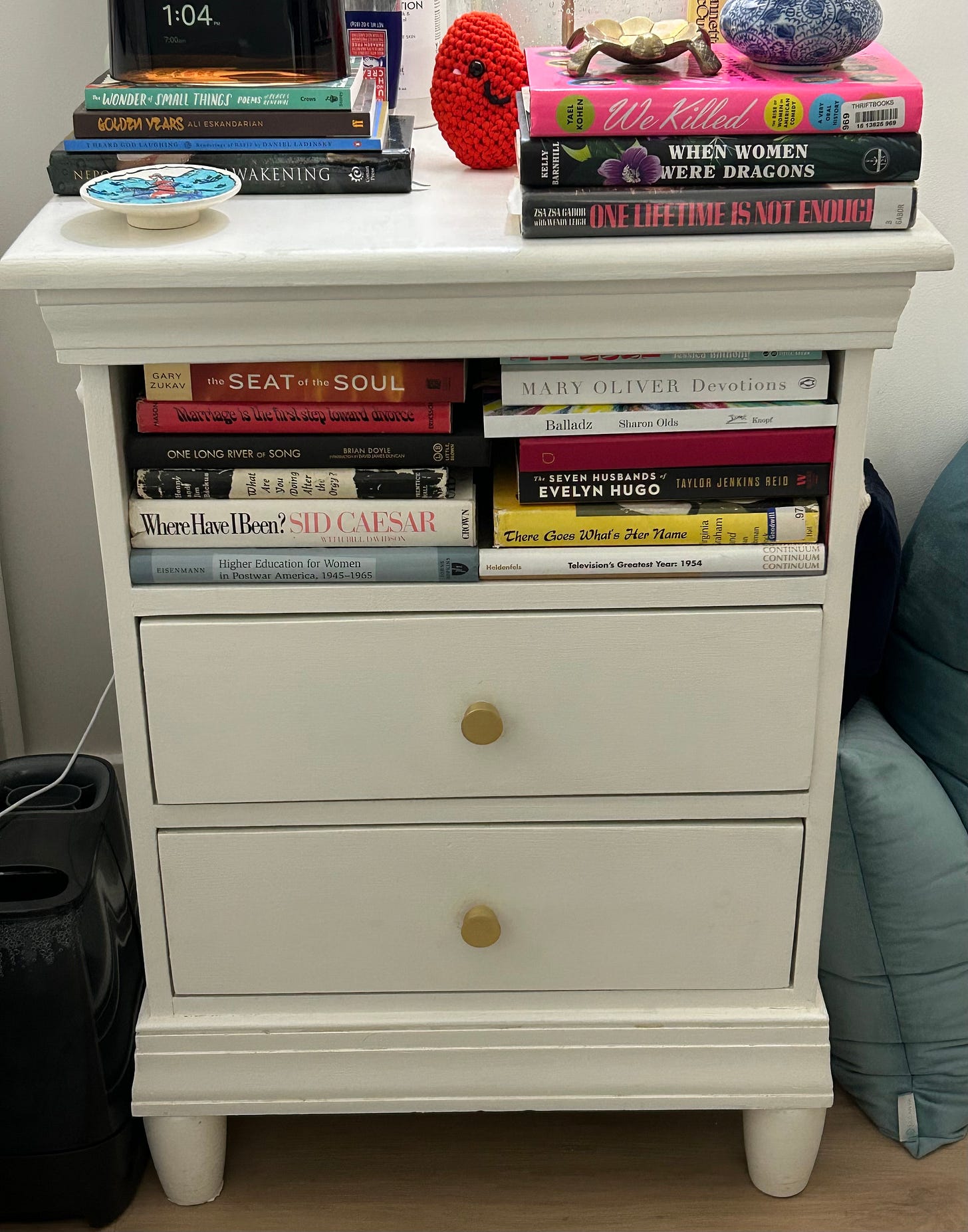

PS. The star of today’s piece!

Truth: One lifetime is not enough.

And that is a fine looking nightstand.

Caroline that’s a keeper! What a beautiful crafted post in memory of your pops.

A month ago we lost my father-in-law and two years my mother-in-law. We have a house full of antiques with no where to go with the heirlooms. Material Girl is giving me pause on this problem.